Spot, Goober, and Other Iguanas Who Saved My Life

Queens, New York, 1970

Sitting in my palm the baby green iguana’s wide-open eye, afraid and curious all at once, peered into mine. His black oil pupil had a thin ring of gold around it. His wispy, banded tail reached my elbow. The way he tilted his head to see the ceiling and the walls, the way he bent down to touch my skin with his pink tongue, the way his sides moved in and out with each breath –his every movement had a timing that I recognized as reptilian.

I had just turned eight years old, and my mother was twenty-three. She wanted to go to art school in Queens, New York, so she moved us there from rural Indiana, where I’d stood barefoot in the mud by the pond holding my bullfrog. When the baby iguana was looking at me, I felt grounded; safe, because I was still connected to the Earth’s web of life even though I was no longer in a place of green plants and many animals, but in one manufactured of concrete for one species only.

The baby iguana, said the care book, was from South America. I held him close –I wanted him to know that I was his friend, and to show him that I knew how he felt being so far from home.

I studied the care book called Know Your Pet Iguana. I remember a photo in it of a red-haired boy with freckles and a smile holding an iguana big as the black ones from the Galapagos in National Geographic magazine, and I believed my baby iguana would grow big like that one day, and I would hold him in my arms. The care book said he should eat lettuce and mealworms and that a clear plastic box the size of a toaster called a Pet Habitat would be fine for him to live in. There was a plastic lid with a handle and air slits that was pink, or maybe blue.

My baby iguana scampered up my arm to sit on my shoulder, and I could feel the slight weight of him there while I drew frogs and turtles and lizards in my sketchbook. When it was time to put him back in the Pet Habitat he tried to cling to my fingers. I had to use both my hands to make him stay so I could shut the lid. At first, he dug at the plastic sides, and he leapt and hung upside-down from the lid, his little curved claws holding on by the air slits. After a while he gave up and sat still, eyes staring. I hated the Pet Habitat, but I was afraid to let him roam free, because the cat would eat him. It had happened before; with the anole lizards my mother bought for me when we’d just moved to Queens. I’d let my lizards sit in sunshine on the windowsill, and the cat got them.

Around that time, there’d been an incident with a girl at school named Debbie. She saw the turtle patch I’d sewed on my dress and told me she had a pet turtle. We left the schoolyard at lunchtime to go see the turtle. Debbie lived in an apartment, like me, only the building was bigger and had an elevator. Her room was dimly lit with one light on the ceiling, and the curtains pulled shut. She put on a Partridge Family record, and it made me anxious because we needed to be on time getting back to school. On her dresser was an oval-shaped clear plastic container half-full of water. The baby turtle dove under when we came near. The inside of the container was shaped to look like an island in the ocean, with a miniature green and brown plastic palm tree. Under the murky water the turtle paddled wildly against the plastic. Debbie didn’t reach in to help him. I didn’t think he wanted her to pick him up, but he needed something. I didn’t believe that Debbie loved the turtle. I asked if I could have him.

“It’s mine,” she said.

We were late getting back to school, and I was blamed for it. The next day Debbie’s mother appeared in the doorway of the classroom, big with an angry face, and she shouted at me in front of all the other kids, and the teacher yelled at me to “stop the alligator tears.”

Debbie and I were not allowed to be friends after that. I was so anxious at school that I went home one day at lunchtime while my mother was in class at Queens College, and I put on one of her dresses and hurried back, reaching up every so often to keep the neckline from slipping down off my shoulder. The minute I walked into the classroom, I knew that I looked ridiculous. It wasn’t until my mother gave me the baby iguana that I felt less alone and out of place at school, because I had a friend of my own at home to think about….

Iguanas showed me my life purpose when I was desperate to find it. They made sure I stayed on a path of fulfilling it, lest the unmet desire burn me to ashes from the inside out. Maybe that sounds dramatic, but it’s real.

Here’s an excerpt from a great piece Annemarie Schuetz wrote for the River Reporter:

Lizard people

Sometimes our people are human. Sometimes they aren’t. Does it matter?

By ANNEMARIE SCHUETZ

https://riverreporter.com/stories/lizard-people,136126?

CALLICOON, NY — Wendy Townsend’s morning starts with a little writing before the iguanas wake up.

“Then I’ll look across the room and see Emo,” Townsend said. “He’ll be really focused on me. On what will happen, on my emotional intentions.”

It’s a survival mechanism, she said. So she pets him, makes contact. Reminds him that she is his human, maybe.

“If I don’t tend to him, he’ll get frustrated and bite,” Townsend said.

Not all iguanas like physical contact, but Emo does. Each of her iguanas is different. They are their own people, and they are her people, a deep connection that goes back to Townsend’s childhood.

Hot Weather Lizard

“I arrived on the planet in love with iguanas,” she said.

Not that iguanas were thick on the ground in the Midwest, where she is from. But there was a bullfrog; then there was a lizard. And from such discoveries a life, a pathway, can emerge…

The Boston Globe has published 2 of my personal essays in their Ideas column.

For now, the book about the Jamaican Iguana is on hold.

A book about the Jamaican iguana.

These two short videos about the Jamaican iguana are awesome!

My book for young readers is called Big Lizards on the Brink: The Fight to Save the Jamaican Iguana

Jamaican iguanas were once so common on the southern plains of Jamaica that the region was called the Liguanea Plain, from the Arawak word for iguana. In the 1940s the last Jamaican iguana was seen on Great Goat Island, and the species was declared extinct. Fifty years later a pig hunter named Edwin Duffus and his dogs caught a big lizard in the Hellshire Hills that turned out to be a Jamaican iguana.

The book will shine a light on the Jamaican iguana’s remarkable comeback, and the people who are working to save and protect him.

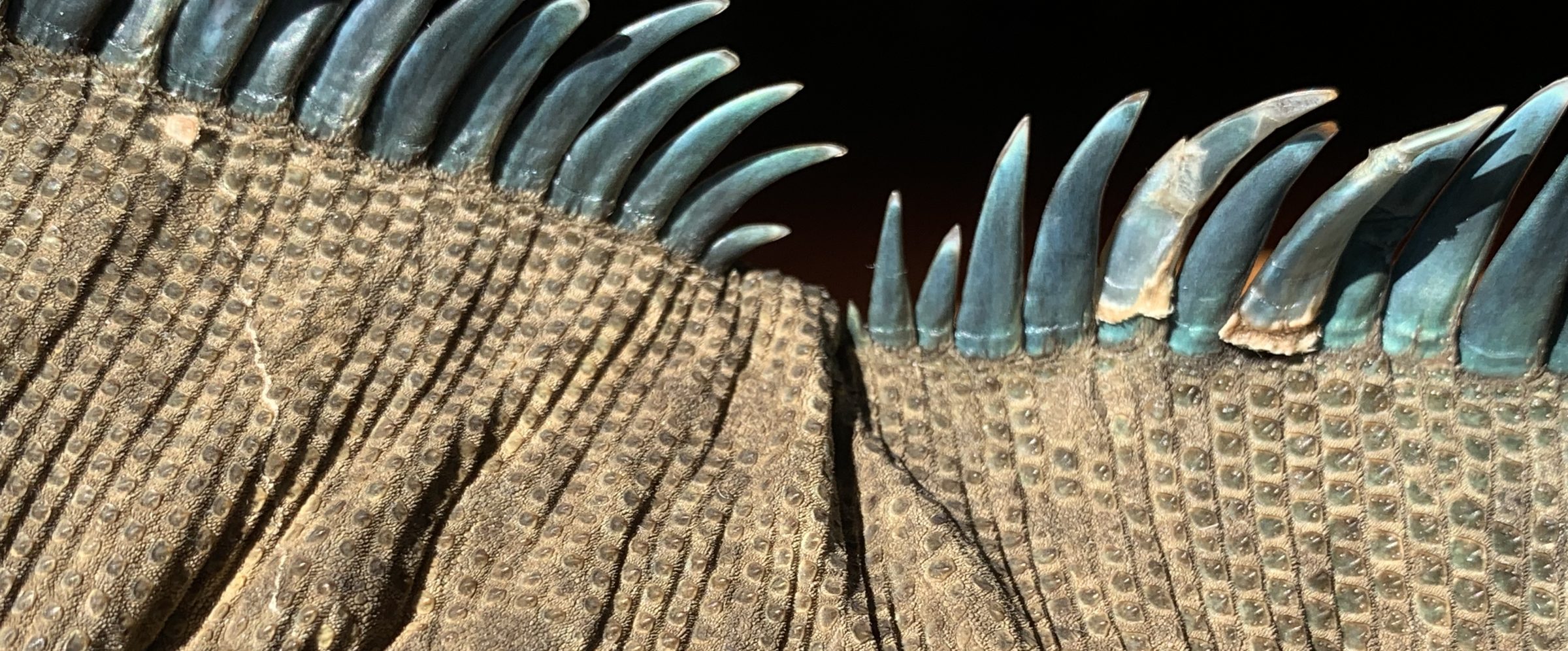

When I say “iguana,” do you picture a big, green lizard with a tall spiky crest and a long, banded tail, like this guy?

He’s a green iguana, and he lives in the rain forest. The scientific name for the green iguana’s genus is Iguana.

But have you ever heard of a rock iguana?

Rock iguanas are big, plant-eating lizards that have adapted to living in the rocky habitats of some islands in the West Indies. The scientific name for the genus which contains all the rock iguana species is Cyclura. The Jamaican iguana’s scientific name is Cyclura collei.

Jamaican iguanas are part of the rock iguanas of the West Indies. As a group, these rock iguanas are the most endangered lizards in the world. Why does that matter? Rock iguanas are a keystone species in a strange and beautiful biodiverse habitat called a dry limestone forest that’s also endangered. Plus, rock iguanas are super-cool. Scientists and zookeepers and field researchers love working with rock iguanas because they are big lizards with big personalities who will hang out with you when they get to know you.

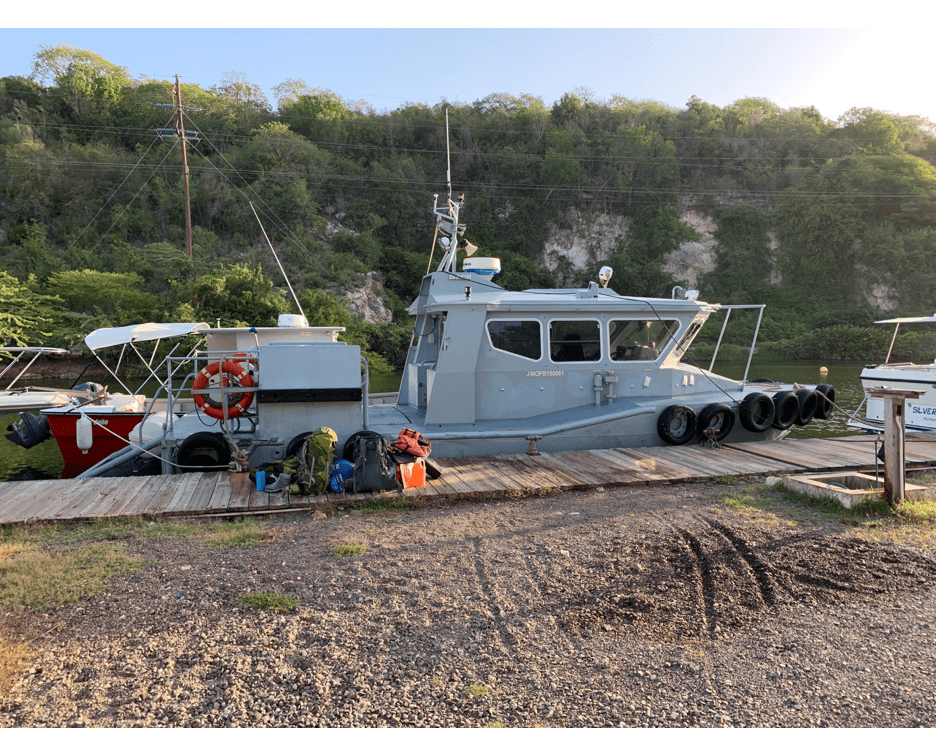

Hoping to see a Jamaican iguana I went to Jamaica in June of 2019. Iguana scientist Dr. Stesha Pasachnik met me at the airport and early the next morning we got on a boat for the two-hour ride to the beach at the foot of the Hellshire Hills.

After carrying our supplies ashore, we pitched our tents under the low canopy of sea grape trees, covered ourselves with sunscreen and bug spray, filled our water bottles and headed out. We walked up the beach past a salt marsh where crocodiles sometimes hung out. The trail was just past the marsh, and we followed it into the forest.

Small lizards scurried in the leaf litter and hummingbirds whizzed past us. Moths with dark patterned wings as big as my hand rested on the leaves of low branches. The trail went over big patches of pocked limestone rock called karst that was not easy to walk on. One slip and you could really hurt yourself on the sharp edges of the karst. Some of the bushes and trees were spiny and tall cacti grew along the trail, so you had to be careful what to reach for when helping yourself climb up a steep part. I was in rock iguana habitat for sure, and excited to think that one of the big lizards could run across our path at any time.

After an hour of hiking uphill, Stesha put a finger to her lips. We silently walked slowly toward a blind that looked like a small shack made of branches and scraps of wood and covered with a tarp. Bobby, an intern with the iguana project, sat in the blind with a notebook on his lap, watching through a panel of mesh. Stesha went to check in with the field rangers and I sat down on a rock nearby. I looked through the panel of mesh and caught my breath.

So much was happening I didn’t know where to look first. Five lizards at least three feet long rapidly dug in the brick-red earth making burrows, pulling it out with their front feet and kicking it up in sprays with their back ones. All the lizards wore a fine coating of the iron-rich red soil. A red plume shot out of a hole as the tail and rear legs of one lizard wriggled out backward part way, then went down to dig some more. Another came out of her burrow headfirst and then she started pushing and kicking soil across its entry. I noticed her sunken flanks; she’d laid her eggs in the burrow.

At the edge of the bushes a big female tried to drive off a newcomer. A small female, slate gray and olive, dappled in aquamarine and turquoise blue, the new iguana did not yet wear her coating of red. Bobby said the little iguana would have to fight extra-hard for space to dig. Closer to the center of the site two females went nose-to-nose, chins and bellies on the ground; bobbing heads in their iguana language to say, this is my nest hole, go dig your own!

At one point ten female iguanas were in motion on the nest site. I watched them strut and face off, rising high up on their muscular legs. Their red-dusted lizard bodies and long tails curved as they turned in half circles to check on their work of digging nests. It was a dance of dragons –and paradise for a lizard lover like me…

That night, I thought about what I’d witnessed at the nest site. It was a ritual that very few people got to see. It had been going on for centuries, but still, I had the sense that the iguanas’ drive to create a new generation was extra-intense, as though they knew how close they’d come to going extinct.

Saving the Jamaican iguana depends on the head-start program at the Hope Zoo and the amazing staff of the iguana reserve, led by Jodi-Ann Blissett. I was thrilled to meet her when I visited Jamaica. She is a born reptile lover, like me.

I got my first pet green iguana when I was eight years old and I have loved iguanas and other reptiles ever since. There was only one year in my life when I didn’t have any iguanas and it was a terrible year. Now I live with three rhinoceros iguanas and two Cuban iguanas named Sebastian, Ava, Emo, and Luna and Che. Each lizard has his or her own personality, and they keep me busy with their ways and the care I give them. They are all rock iguanas, and cousins of the Jamaican iguanas. When I went to Jamaica to research this book, the Jamaican iguanas often reminded me of my iguanas, and so I wrote about my observations and experiences in My Iguana Notebook. I’ll share some of those observations with you throughout this book.

I hope this book will inspire you to not only appreciate iguanas, but to start a notebook of your own where you can write or draw your experiences with family pets, or animals outdoors. All you need is a notebook or sketch pad, a pencil or pen, and your eyes, ears, and heart.

My Iguana Notebook

On a warm spring day in 1993 around the time that a pig hunter named Edwin Duffus would find a Jamaican iguana, I was in Big Pine Key, Florida, stepping inside a cage where a rhinoceros iguana named Mao and his mate, Gretta lived. Rhinoceros iguanas and Jamaican iguanas are cousins. The cage was 18 feet by 12 feet, furnished with big limestone rocks, a long, thick tree branch and several cacti.

Mao and Gretta were finishing up their lunch of shredded greens, veggies, and fruit. I sat down on a rock and Mao followed me. He placed one of his feet on my left foot. I remember looking down at his black foot –his hand, really—and how it nearly covered the toe of my white sneaker. Mao began to stand on his back legs to climb into my lap, and I reached down to help him up. For a moment I leaned back slightly from his head that was as big as both my fists put together and just inches from my face. I looked at the long lines of his strong jaw, aware of the many sharp teeth inside his mouth. Lizards and dinosaurs diverged millions of years ago, but I still felt like I had a dinosaur in my lap.

Mao’s belly was warm from the sun and he was heavier than my cat. I stroked his back and around his chest and head. The small scales of his skin felt like raw silk, but alive. He tilted his head and he peered into my eyes with his gray ones. My throat tightened and my eyes filled from the emotion of connecting with another being. We looked at each other like that for a few moments. I didn’t want to ever leave Mao and I promised myself that one day, I would live with rhinoceros iguanas.